This is my latest post on the AAFP’s Fresh Perspectives Blog. You can also check out my recent Scope Radio podcast on this topic with Erin Fox, PharmD.

Reggie is a spunky, 38-year-old patient of mine who makes my clinic day more enjoyable. His collection of chronic health problems — including type 2 diabetes, near-complete hearing loss, bipolar disorder, active hepatitis C from prior IV drug use with no current liver fibrosis and chronic migraines — certainly make life more difficult for him, making his buoyant personality all the more remarkable.

Reggie and I have been working on these conditions since I started practice a few years ago — well, except for the hepatitis C, even though he does have a treatable strain. Because many of his other conditions would likely be significantly worsened by the standard treatment regimen of interferon and ribavirin, he has never been a good candidate for therapy.

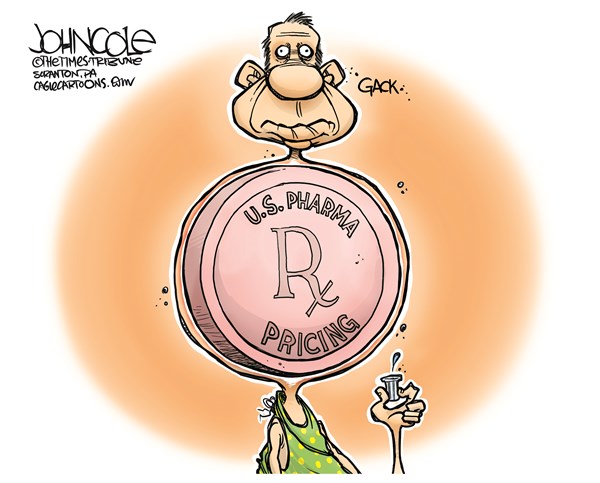

Likely every family physician has stories like this, whether about patients with hepatitis C or other conditions requiring expensive medications. If every person in Utah afflicted with active hepatitis C disease were to receive treatment with Sovaldi, it would consume the entire Medicaid budget for my state. The average cost of medications for complicated conditions such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis is now higher than the median household income in the United States. So it’s no surprise that rising prescription drug costs are now the biggest health care concern for the general public.

After years of ignoring the problem (and, in some cases, contributing to it), politicians and policymakers have started discussing the crisis. HHS recently hosted a summit on prescription drug prices. Presidential candidates have weighed in on the topic in their stump speeches and debates. A Senate committee recently grilled President Obama’s nominee to head the FDA on this issue. All this may or may not lead to change, but at least the issue is reaching a national level of discourse.

But what has led to exorbitant price increases in medications? Why do Americans pay so much more for the exact same medications than do patients in other countries? There are multiple likely culprits:

- Price of innovation — It simply costs money to come up with new, effective medications, but how much is “reasonable” for a company to spend on research and development of new drugs is a controversial question. Many think that the investment drug companies claim to make in R&D is an excuse to reap higher profits, whereas others argue it is simply the cost of doing business.You can imagine my excitement when many new treatment regimens with considerably fewer side effects began receiving FDA approval, beginning with sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) and simeprevir (Olysio) in 2013. I began coordinating with a hepatologist at that point to get Reggie the care he needed, but we quickly discovered that none of these regimens would be approved for him because of the exorbitant cost, reportedly more than $84,000 for a 12-week treatment course. Reggie is covered by both Medicaid and Medicare, but neither payer would cover the cost because, ironically, his disease had not yet progressed far enough.

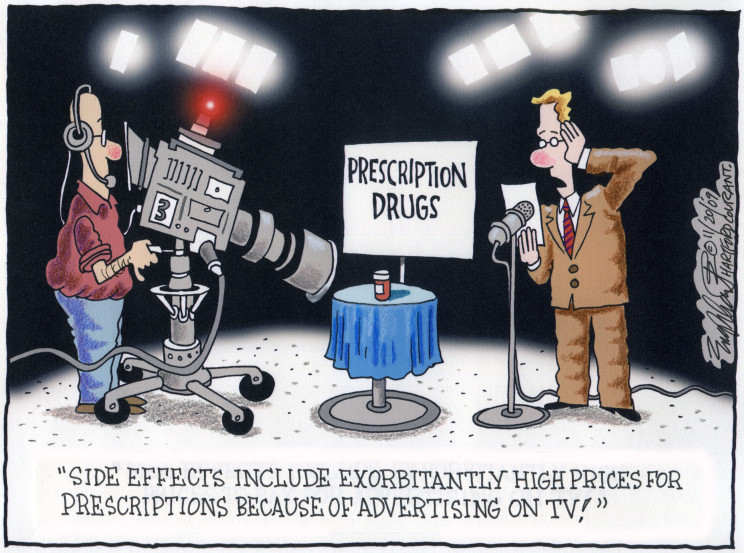

- Direct-to-consumer advertising — The FDA loosened regulations on advertising pharmaceutical products directly to patients in 1999. There has been a significant increase in drug prices since that time, but it is unknown if the agency’s action was the cause. The AMA recently came out against this practice as have many patient advocacy groups, and the AAFP says direct-to-consumer ads should not mention prescription drugs by name.

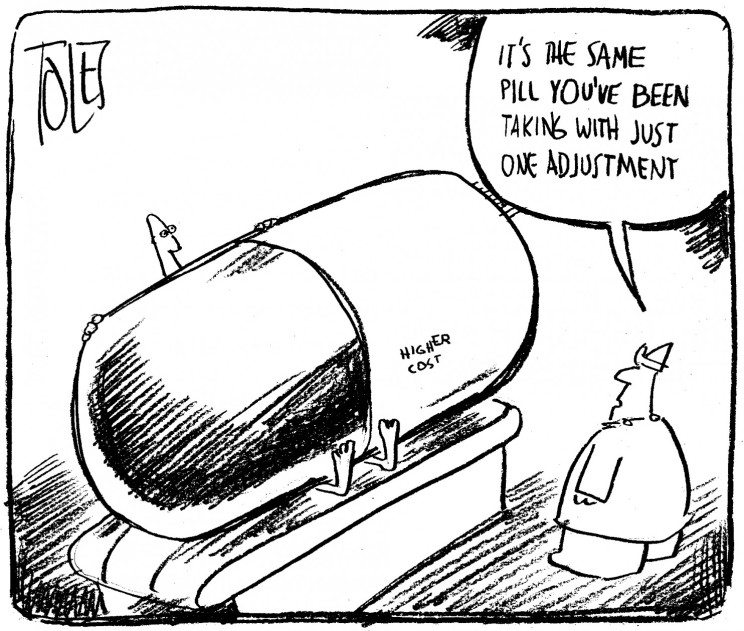

- Patent laws — Many laws passed during the past two or three decades have lengthened the life of pharmaceutical patents. This keeps generic medications from coming to market until much later, allowing the developing company a larger profit on its product. And 27 percent of generic medications increased in price in 2013, including the long-time generic medications doxycycline and pravastatin. Because of this, it is unclear if changing patent laws would significantly decrease prices. Nevertheless, the higher prices of brand name drugs remain under the purview of the pharmaceutical company for many years.

- Changing insurance market — The long-term trend in health insurance is leading to more out-of-pocket costs, including those for medications. Patients may be simply more aware now of the high costs of medication.

- Medicare restrictions on price negotiations — Medicare is prohibited from directly negotiating drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, leading to significantly higher prices compared with those of national systems in countries that do negotiate prices. Correcting this is one of the most widely discussed potential solutions, likely because it is in direct control of the federal government, and because the bulk buying power of Medicare could significantly alter drug costs in the United States. For these reasons, it is my opinion that this is the most likely first step to be taken in addressing the problem.

- Reimportation ban — It is illegal to reimport medications from other countries for cheaper sale. Many Americans do travel elsewhere, particularly to Canada, to buy prescription drugs, but opponents claim that raises potential safety issues. Whether that is a significant concern or not, the limited supply of medications in other countries makes reimportation an unrealistic solution on a broad scale.

So what about Reggie and treatment for his hepatitis C? I have tried multiple avenues, but there is likely no hope for getting any appropriate regimen covered for him at this time. There is a limit to what I can do for my patients. Many pharmaceutical companies offer rebate or discount programs for medications, and occasionally, direct appeals to insurance companies (beyond prior authorizations) can be successful, but there is no easy fix to this problem.

Considering the immense power of the pharmaceutical lobby, the solution may need to come from patients up, instead of from the government down.