Commencement addresses are hard to give and often boring for the audience. But I can unequivocally say that this is the best address you have ever heard!

Welcome to the University of Utah Family Medicine Residency Graduation 2024.

Commencement addresses are hard to give and often boring for the audience. But I can unequivocally say that this is the best address you have ever heard!

Welcome to the University of Utah Family Medicine Residency Graduation 2024.

This is my latest post on the AAFP’s Fresh Perspectives Blog. You can also check out my recent Scope Radio podcast on this topic with Erin Fox, PharmD.

Reggie is a spunky, 38-year-old patient of mine who makes my clinic day more enjoyable. His collection of chronic health problems — including type 2 diabetes, near-complete hearing loss, bipolar disorder, active hepatitis C from prior IV drug use with no current liver fibrosis and chronic migraines — certainly make life more difficult for him, making his buoyant personality all the more remarkable.

Reggie and I have been working on these conditions since I started practice a few years ago — well, except for the hepatitis C, even though he does have a treatable strain. Because many of his other conditions would likely be significantly worsened by the standard treatment regimen of interferon and ribavirin, he has never been a good candidate for therapy.

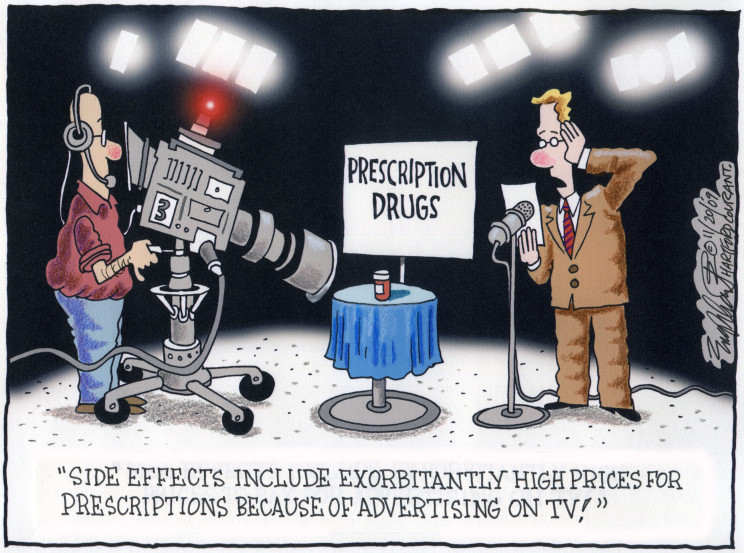

Likely every family physician has stories like this, whether about patients with hepatitis C or other conditions requiring expensive medications. If every person in Utah afflicted with active hepatitis C disease were to receive treatment with Sovaldi, it would consume the entire Medicaid budget for my state. The average cost of medications for complicated conditions such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis is now higher than the median household income in the United States. So it’s no surprise that rising prescription drug costs are now the biggest health care concern for the general public.

After years of ignoring the problem (and, in some cases, contributing to it), politicians and policymakers have started discussing the crisis. HHS recently hosted a summit on prescription drug prices. Presidential candidates have weighed in on the topic in their stump speeches and debates. A Senate committee recently grilled President Obama’s nominee to head the FDA on this issue. All this may or may not lead to change, but at least the issue is reaching a national level of discourse.

But what has led to exorbitant price increases in medications? Why do Americans pay so much more for the exact same medications than do patients in other countries? There are multiple likely culprits:

So what about Reggie and treatment for his hepatitis C? I have tried multiple avenues, but there is likely no hope for getting any appropriate regimen covered for him at this time. There is a limit to what I can do for my patients. Many pharmaceutical companies offer rebate or discount programs for medications, and occasionally, direct appeals to insurance companies (beyond prior authorizations) can be successful, but there is no easy fix to this problem.

Considering the immense power of the pharmaceutical lobby, the solution may need to come from patients up, instead of from the government down.

I recently published my second piece on what I call “Costco Health Care”. This latest one is at the AAFP’s Fresh Perspectives Blog, whereas the first was at Physician’s Practice. While the two articles are actually quite different in their approach, the common link between them is the waste that we have in our health care system. Unfortunately, a lot of this is unrecognized without hindsight, but the majority of it is known beforehand.

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets,” and the US health care system is the least-efficient, least consumer-centric industry in the developed world. It’s an extremely convoluted system, with so many superfluous, redundant, confusing, expensive, and deleterious parts, that very few experts/analysts actually understand it! (see Ezekiel Emmanuel’s Reinventing American Health Care for a full explanation of how few people really get it.) To identify such an industry as socialist misunderstands the lack of central organization in it’s structure; to identify it as capitalist ignores the presupposition that the consumer can have full understanding of the implications of their “rational” choices. The system is (and likely ever will be) fully caught in the middle of these two ideologies and can thus never experience the benefits of either, but likely just the harms of both. Hopefully we can at least keep Costco in its intended economic role, instead of permeating our health care system.