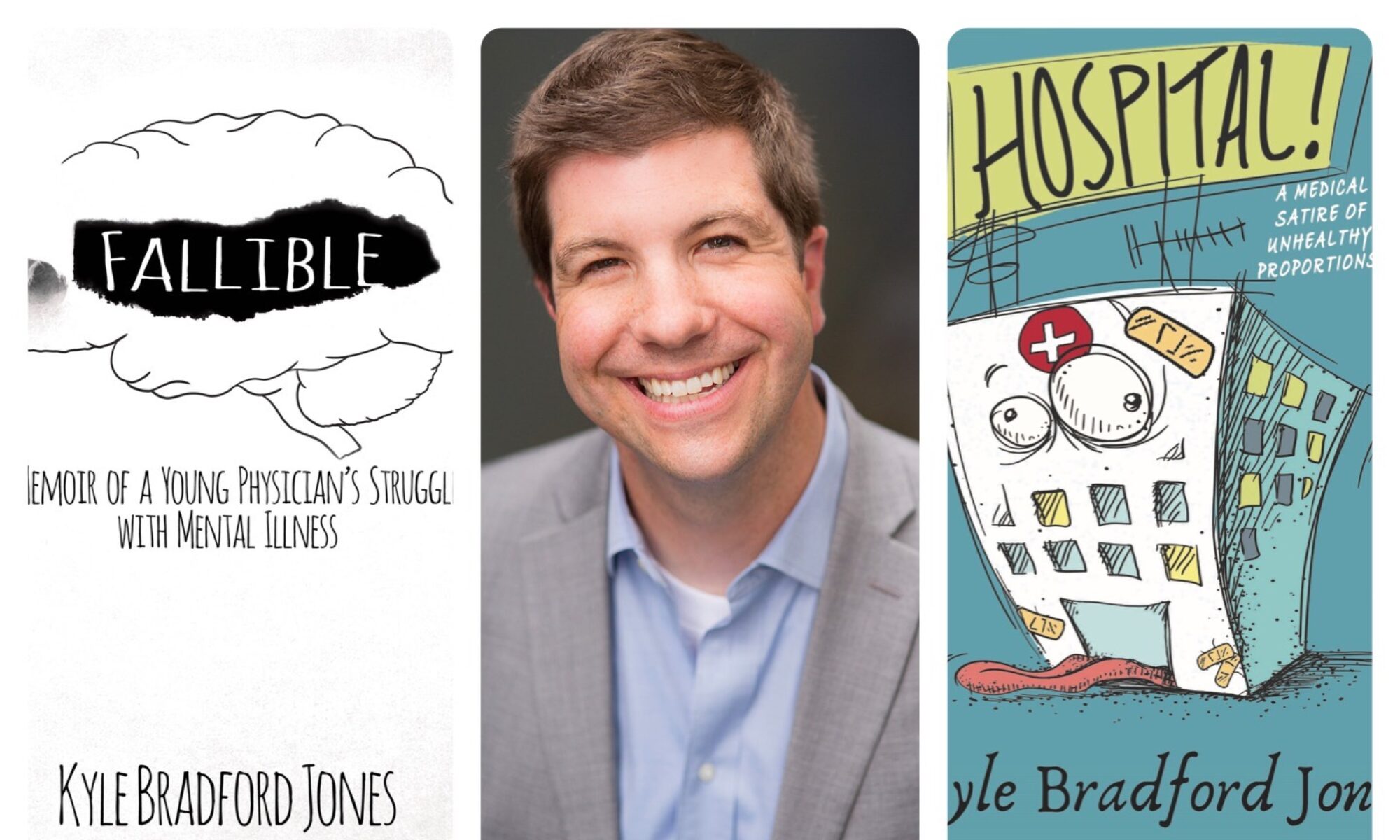

In honor of the beginning of the baseball season, here is an excerpt from my book Fallible: A Memoir of a Young Physician’s Struggle with Mental Illness about the joys and struggles of trying to be a little league hero. Make sure to buy your copy of the book and enjoy this excerpt!

As I stepped into the batter’s box, all I heard was my own breathing. I was looking pretty cool with my fairly new left-handed batting glove. It was black like a ninja suit, sleek in the twilight, though it probably didn’t intimidate anyone. No matter. In my mind, I exuded complete confidence, even though I knew I didn’t have any. I made a sort of pre-swing ritual, tapping the plate with the bat or wiggling it over my feet, combining the styles of multiple professional players. I watched baseball all the time, knew the routines of all the best players in the game. Maybe the reason I’m not better at baseball is because I don’t more accurately mimic Barry Bonds. Kirby Puckett was my favorite player, but his quick bat-wiggle and constant shifting of weight between his feet in the batter’s box was more than a little awkward to replicate— my impression looked more like a waddling penguin waving a flag. Wade Boggs would scribble some Hebrew word in the dirt before stepping into the batter’s box. That must be my problem—I don’t know Hebrew. Why hadn’t I been born Jewish? I blamed my parents.

These rituals are supposed to calm you, focus your thoughts, and appease your anxiety. If you have played baseball every day for years, that probably works. But it more likely made things worse for me, because it crystallized my presence in the path of an out-of-control pitcher in a pivotal moment of the game. His head rose above the elevated peaks behind him, making him appear nearly twice as big as I was. The literal five-o’clock shadows from the setting sun almost made it look like he was growing a beard. We were only ten years old, how in the world did he have a beard already? Did he have some disease? Did I have some disease? I would most assuredly die if the ball hit me, since the stalling of my puberty compared to his put me in greater danger.

It was the final inning. There were two outs and two runners on base. We were down by one run. I wanted to be anywhere but there. To say that my heart was beating like a jackhammer doesn’t effectively articulate how slow a jackhammer moves compared to a ten-year-old boy’s anxiety. The adrenaline flowed freely through my veins like the endless stream of sunflower seeds spit from the players’ lips. I didn’t like adrenaline. It made me nauseated. It made my knees weak. It made me need to pee. That would be one good thing about striking out—I could use the bathroom sooner. That might take away the sting of the shame and embarrassment I was about to experience. But that also betrays my mindset in athletic competition—I had already decided that I would be out.

I had experienced some nightmares about situations like this. Even though I loved baseball, the potential for moments like this were outweighing the excitement it brought me. All I needed was a single to bring in a run or two; I could surely manage that, right? But why weren’t my teammates better hitters or base-stealers? They could have saved me from this moment. I blamed them for my predicament.

The crowd was a contemptible assembly of entitled parents who assumed their son would be in the majors if only he would just listen to what I’m telling him to do right now, or the stupid umpire realized my son’s entire future is at stake here, or the moronic coach would just let my son pitch instead of playing right field all the time.

Thankfully, that didn’t describe my parents; they knew I sucked, and they loved me anyway.

The crowd contrasted the lovely venue, with the setting sun adorning the rising mountains. The trees surrounding the field blocked what remained of the sun, so what I saw from the plate was the majestic calm of the reassuring palisade. The halcyon beauty of baseball was on full display. I had lived next to the mountains nearly my whole life, so I took their allure for granted. The peaks are close—one could drive there and be on a great hike within fifteen minutes from my house. That probably provided some subconscious stability in life, a comforting source of protection and assurance. But I didn’t really care about such splendor at present—in this moment, the mountains served only to amplify the pressure that I felt bearing down on me as if I were an ant being buried by a growing hill.

The first pitch came in right down the middle, a meatball that any good player would crush for a double— or even a home run. I backed out of the batter’s box as the pitch arrived, assuming any pitch near home plate would hit me. Strike one. This is when I started to get “coaching” advice from multiple spectators.

“Strong swings, crush that ball!” “Wait for your pitch!”

“Don’t let those good ones go by!” “Big hit! We need a big hit right here!”

“Don’t screw up!” I think that one was from my disdainful older brother, none too pleased to have to be at his ten-year-old brother’s Little League game. And he was seventeen, which meant he hated everything.

It probably goes without saying, but ten-year-old pitchers are not skilled at throwing strikes. The ball can go anywhere and hit anyone in the broad vicinity of home plate; I once even saw a pitch go nearly ninety degrees and hit the dugout fence. The batter ahead of me wasn’t much better than I, but he quickly drew a walk. Lucky jerk: he didn’t have to swing; the pitcher and umpire did all the work for him. My primary concern was avoiding getting hit by a pitch. Getting hit by a hurtled baseball hurts, even when it’s “only” going as slowly as fifty miles per hour off the hand of a young pitcher. Did that physical pain pale compared to the more definitive failure of striking out?

I had already decided to swing at the next pitch hoping to get a hit. I usually had to make this decision before the pitch came in as opposed to looking for its location because I struggled to interpret the ball’s path in the split second I had. Major league batters have less than 0.4 seconds to recognize where the ball is, decide to swing, and go through the mechanics of hitting once a pitch is thrown. Yet somehow they do it, deciding not just to swing the bat but know where to swing to make contact and drive the ball where they want it. I couldn’t fathom that. Obviously, I’m not seeing a pitch come in at ninety- five miles per hour with someone who has reasonable control and at least some predictability. But to me, a pitch well under fifty miles per hour wouldn’t have made much difference—I had less than no time to decide to swing.

Just my luck, the pitch wasn’t anywhere near a strike. My swing was futile, a lunge at respectability that ended in an abject poverty of spirit. I was down to my last strike, and I had already mentally gotten myself out. The ball bounced in the dirt ahead of home plate. There is no way that anyone would swing at such a laughable pitch. In times like this, I often listened to the play-by-play broadcasters in my head.

“Boy, Jones is really struggling tonight. He looks as if he has no pitch recognition whatsoever. That last swing was slow and weak; I don’t think he can catch up to these fastballs he’s seeing. He’s not even getting much heat from the pitcher, but it doesn’t seem to matter. He looks so uncomfortable in the box, even though he looks so cool with his batting glove.”

The “color man” on the broadcast chimed in: “This pitcher has been pretty wild. I think Jones should just take these pitches instead of guessing where they may be going. This is such a critical situation in the game that you don’t want to get yourself out by getting into your own head too much and making mental mistakes. He should step out of the box, take a deep breath, and calm himself. This is one of those moments that defines what type of ball player you’ll be. Some thrive in this pressure, some wilt. He’s definitely wilting. His face shows his fear way too much— he looks like he wishes this was all over.”

Then came the encouragement from the crowd as their panic began to match mine.

“Come on, you can do this!” “Keep the game alive!”

“Finish him!” I think this last one was for the pitcher, but I wasn’t sure.

I wasn’t going to swing at this last one. Most pitchers my age throw more balls than strikes, as opposed to a good major league pitcher, who will throw about twice as many strikes as balls. The odds were definitely in my favor. I should be fine not swinging, right? The announcers on my internal broadcast were right—just take the pitches and make the pitcher get me out. The pitch was coming. Oh crap, oh crap, oh crap, oh crap.

The ball emerged out of the pitcher’s hand in slow motion. I was immediately enveloped in the endless haze of eternity, where the wisdom of the ages resides in the blink of an eye, and I watched as the ball came at me. I saw all my doubts and terrors as though sentient, dynamic entities coming for me. The lifespan of my anxieties was indeed finite despite their grotesque guise and powerful perseverance. Eternity swallowed me, and I knew everything and nothing at once, felt it all but was left empty. The glory of heaven and the ravages of hell emerged in that fraction of a fraction of a second to tell me I was something not entirely different from anyone else—someone who would be razed to the ground repeatedly so as to be raised from the ground repeatedly. I would become as strong as I wanted, even though the weights would still be on me. I could push the boulder to the top of the mountain if I stuck with it and was willing to start all over again once it fell back down. The rock that drags me to the depths of the ocean will eventually wear away. My worries of school and girls and grades and friends and the dark and bullies and physical pain and humiliation and loss and being lost and lost and lost and never found surrounded me, and I somehow found it all freeing. It was as if my internal mysteries were opened by a distorted and fractured key; at least they were unlocked. When the pitch arrived, despite its prior perceived lumbering pace, I wasn’t even sure if it was a ball or a strike. This one was audible, a high-pitched dog-whistle of a ball hurtling past me, instantly breaking my trance and snapping me back to reality. Dog whistles are weird, I thought in that split second. Why can dogs hear them when we can’t? And why did they seem to respond to the whistles so well? Would dogs come running toward this pitch? I wondered how the broadcaster would work that in to the teleplay. And why did they call the other guy a “color man”? Wasn’t that a bit racist?

No matter how the announcers would call it, the game was over. There was no joy in Mudville. At least I could go pee now. I don’t know if my mind was racing or devoid of all thought, but I hung my head as I walked back to the dugout, underscoring the disappointment I felt for letting my team and their blood-thirsty parents down. The announcers in my head chimed in again:

“Sometimes players make their own future. I think Jones’ obvious fear was a self-fulfilling prophecy—he was out before he even walked to the plate. It’s too bad to see that, especially in such a handsome, brilliant, incredibly gifted kid. I think he’s just relieved it’s over. Too bad—he could’ve been the hero.”

But then I heard my brother yell above the agitated crowd: “Don’t worry, Kyle, you’re still a good-looking guy.”

I wasn’t sure if this was more of his sarcastic wit or a sincere support for his younger brother wrapped in jest. Either way, he was flippant enough to yell in front of everyone how it didn’t matter if we lost the game; thankfully, some semblance of my personal worth remained. What happened here did not define me or my team. There was more to me than a momentary show of poor athleticism. It hopefully reminded us all that there was more to life than baseball. Evidently, there was also personal appearance.

If only the girls also felt that way, I might have found some comfort in his support.