Last week on Wednesday April 15th was Jackie Robinson day, celebrating the 68th anniversary of the first modern day African-American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) (there had been a small number of others prior to the current MLB professional system). Like most of us baseball fans, I love seeing all players wearing #42 in his honor, this being the only number retired by MLB as a whole but allowed to be worn on this one day a year. Jimmy Rollins, shortstop for the Los Angeles Dodgers, recently wrote about what a thrill it would be to wear that number while playing for Jackie’s Dodgers, an experience he has for the first time this year (log in likely needed for article).

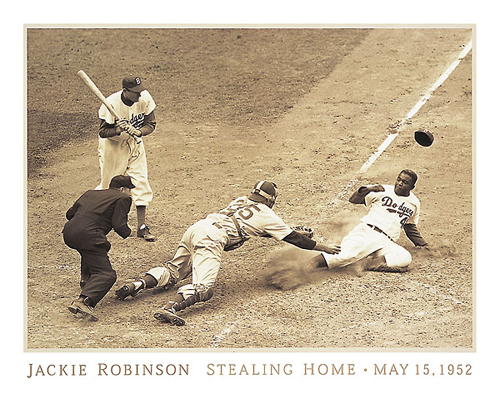

Jackie Robinson has been my hero since I was in elementary school, either the 4th or 5th grade. I read Stealing Home: The Story of Jackie Robinson, a Scholastic Biography by Barry Denenberg aimed at kids my age. I don’t remember how I came upon it, though being a big baseball fan it wouldn’t have been hard for me to pick it up seeing it at the library or book store. The first thing that really caught my imagination was that thought of stealing home, such a lost art of the game in the early ‘90s (and on through today), having seen that iconic picture of him hook sliding into home against Johnny Pramesa in 1952, his hat flying off and his teammate watching on, filling me with immense excitement.

But as for so many of us, Jackie’s story has inspired me immeasurably. Having to be yelled at, taunted, sworn at, thrown at, spat at, ridiculed, hated, spiked, received multiple death threats to him and his family while being completely alone in this endeavor and not being able to give into his natural instincts of fighting back or responding brings me to tears whenever I think about it. I love him for his courage, for working towards something that was bigger than him (or baseball), for being willing to go through all of that. He was truly amazing.

These experiences were shared by many more than just Jackie, both in baseball and outside. But generations of African-American struggle were personified and epitomized in him. He obviously prepared and foreshadowed the remaining civil rights movement in this country, providing more liberty and opportunity for the descendants of those who were physically enslaved by allowing other courageous men and women to free themselves and all minorities from societal enslavement. It all could have blown up if he had behaved differently.

The thing that really sold this was that Jackie could play; if he couldn’t, none of the other stuff would have mattered. He has also been credited with starting a revolution in how the game is played. Those from the Negro Leagues who came to MLB after him furthered this free-styling, risk-taking, hard-running, slap-and-dash method of play, what would commonly be referred to today as small-ball. Buck O’Neill, the late great spokesman and advocate for greater knowledge about and appreciation for the Negro Leagues, describes it as something close to jazz. Many, myself included, would call this a much funner way to play and watch baseball. “There was a lot wrong with the world, but we weren’t sad, man. We had the time of our lives,” said Buck O’Neill about those days.

I have also had much more interest in the Negro Leagues in recent months. Part of it is because of my love for Jackie, part of it is because I travel to Kansas City a few times a year and get to visit the Negro Leagues Museum, part of it is because if you’ve ever listened to Buck O’Neill how can you NOT love the Negro Leagues! It’s characters, it’s history, it’s BASEBALL is full of wonder and excitement. Its “separate but equal” place in baseball history should not be forgotten nor neglected. “We overcame, see. That’s the lesson of the Negro Leagues,” said Buck O’Neill on another occasion.

Both Jackie and the Negro Leagues led to not only more African-American players, but also many Latino players, who have left their own indelible mark on baseball. Roberto Clemente, who had the 60th anniversary of his first game played on April 17th and a huge pioneer in his own right for the racism he faced and overcame, chose number 21 because he hoped he could be “half the man” that Jackie Robinson (#42) was. Robinson Cano, by far the best 2nd baseman in MLB today, was named after Jackie because that is who his father’s hero was. Many other Latino ballplayers now participate in what we greedily refer to as “our” national pastime, and do so with many similar challenges, though to a far lesser extent, than what Jackie experienced.

But the best way that civil rights and baseball intersect is an experience Joe Posnanski had with Buck O’Neill while writing a book about Buck near the end of his life. Buck had just spoken at a press conference in Washington, D.C. to request national designation to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Buck needed to take a break in a backroom after speaking. Here is an excerpt from The Soul of Baseball (one of my favorite books, and definitely one of the best baseball books ever written):

“’Hold on for a second, hold on,’ Buck said, and he pointed at a television nearby. ‘You know something funny? Look at that television. You know, if the Willie Mays catch was on right now—the one from the World Series—everyone would stop and watch it.’

“Everybody around stopped and listened to Buck. He was talking about the catch Mays made at the Polo Grounds in the 1954 World Series, the one where he turned his back and raced toward the wall on a long ball hit by Vic Wertz. Mays ran full speed to a spot and somehow caught the ball over his head without even looking back. His hat flew off. And then, in one motion, Mays whirled and threw the ball back to the infield. Jack Brickhouse, the announcer, screamed that it must have looked like an optical illusion to a lot of people. More than fifty years later, most people would say it was the greatest catch ever made.

“’How many times have we all seen that catch?’ Buck asked. ‘And yet, if Willie Mays was up there on the television, this whole place would come to a stop.’

“’If Willie was up there, people would stop making laws. They would stop running. They would stop arguing about little things. Or big things. No Democrat or Republican, no black and white, no North or South. Everyone would just stop, watch the TV, watch Willie Mays make that catch. That’s baseball, man.’”

That’s what baseball means to civil rights. Jackie sliding into home against Yogi Berra—the wonder of baseball and nothing else—still represents that to me.