I recently wrote about who does, and who should, own patient records at the AAFP’s Fresh Perspectives. This topic is more controversial than I think it should be. It’s your body, it’s your information, it’s your blood, it’s pictures of your body, it’s yours. It’s time to get rid of medical paternalism and move to more shared decision-making (but that’s a topic for later on). In short, I don’t see this as an issue, and I think it is inevitable that patients will own their records in the relatively near future.

Merry Christmas, Regina

The average person has about 500 million alveoli, microscopic sacs in the lungs where gas is exchanged in the body. In this location, oxygen moves into the blood to be used by our physical organs, and carbon dioxide transfers into the lungs to be breathed out. Chronic lung diseases such emphysema and chronic bronchitis erode the structure of these alveoli, leading to the feeling of shortness of breath as oxygen is not shifted into the blood very effectively, and carbon dioxide subsequently slowly builds up in your body. Various inhaled medications can help slow down the deterioration, but continuous oxygen is often needed and infections are very common as the lungs find it more difficult to properly recover from common organisms. The prevalent belief among the resident physicians at the formerly known as Her Holy Name Hospital was that Regina only had about three of those 500 million alveoli left. How she was still alive, none of us really knew.

The stench of Regina’s Designer Imposter perfume filled the emergency department, alerting all of its inhabitants to her presence. It was quite a miracle that the perfume didn’t overwhelm her few remaining alveoli, but then the smoke from her cigarettes probably blocked the fragrance from getting that deep in her lungs in the first place. It was unfortunately an all-too-familiar smell in the hospital. The 62 year old woman came here about every 1-2 months due to an exacerbation of her chronic emphysema, which required stronger medications and oxygen concentrations for a short time. I had only been an intern for about 6 months and I already knew her quite well.

This hospital visit occurred 2 days before Christmas, along with large amounts of snow and extremely cold weather. I was an intern working long hours in the hospital, and I was not looking forward to working on Christmas day. Obviously someone needs to work in the hospital on Christmas, and interns are the lowest of all grunts to fill that need. Evidently this “educational imperative” provides some sort of professional character. We’re also very cheap labor.

I had not spent much time with my wife and two sons in recent months, and my absence from home on Christmas would mean that they might all share the same disturbing thought that I myself occasionally had, that I may not still exist in any meaningful way, at least not as it concerned my family.

That being said, I actually found Regina’s salty demeanor and frequent smoke drenched yelling somewhat charming. It had the opposite effect on most people, having proven to be the main cause for driving away all of her family and friends from her life.

“Where is the doctor?!? I need my medicine!” she yelled from her curtained-off room in the ED. Her breathing trouble evidently wasn’t bad enough to keep her voice from carrying.

Her frequent hospitalizations usually occurred when she received a new disability check and could buy her carton of cigarettes. She was unable to resist smoking more than usual just after purchase than to evenly ration it until she could afford more. The extra smoke was too much for her diminishing lungs to take. This was combined with the difficulty in getting her inhaled medication from the pharmacy. The carton of smokes was half a block away, the pharmacy about a mile. It was much easier to call the ambulance and go to the hospital than find a ride to get the medications that would prevent the need for such extreme measures.

The timing of this ED visit was somewhat suspicious as she usually got her check at the beginning of the month, and she didn’t seem to be breathing as poorly as with her typical inpatient stays. I didn’t think too much about it, but proceeded with collecting the history of recent health events and examining her.

The Family Medicine team had already developed its emblematic, caustic cynicism with her as we tended to do with all “frequent fliers”. This feeling was largely born from the judgements inherent in frequently caring for people who had been largely responsible for their chronic health problems, in her case with smoking. This frustration also arose from a subconscious recognition that there was nothing we could do to help her condition long-term, just provide a periodic “tune-up” before sending her back to an empty home filled with heartache. It was a well-earned contempt, though not entirely justified. It was a hollow, lonely feeling of failure for us residents.

“I don’t want a nicotine patch, I need someone to take me outside for a smoke! I’ve been here before, I know how this works, now GET ME A DAMN AIDE!”

Yep, charming is the word.

“Are you sure there isn’t something you can do to get out of working on Christmas?” My wife was trying every possible angle to get me home to be with my kids. I completely understood; I would love nothing more than to stay home. But the result of her constant lamentations had the result of making me feel guilty for skipping out on my family.

“I’m sorry dear, there’s nothing I can do. It looks like we’ll have enough patients that we need the whole resident team there. Hopefully I’ll be able to leave early, but we’ll have to see how it goes.”

I made sure to spend as much time with my boys in my abbreviated evenings before Christmas, hoping that would somehow impress positively upon their young psyches.

As her case was discussed with the team, everyone else noticed the unusual timing of her ED visit and relatively mild symptoms (“relatively” for her, anyways); this hospitalization was because she didn’t want to be alone on Christmas.

Her husband had passed away long ago. She had a son and a daughter, but neither lived in the state. Not only that, but their last interactions had not been pleasant, leaving Regina to wonder if she would ever see either one of them again.

“Good riddance, if you ask me.”

She put on a stubborn, apathetic front, but behind those sullen eyes the pain was apparent.

She had some friends previously, but as with her family, the pattern was repeated—she drove them away. I wondered if she knew how not to drive others away. But her doctors and nurses couldn’t be driven away due to our oath and the law, so she came to the broken hospital for some fractured companionship.

As Regina’s current condition was not too significantly worse than usual, she was ready to go home on Christmas Eve. The problem was that she didn’t want to go.

“I still can’t breathe, and you’re sending me home?!? You can’t send me home yet! Come on you stupid little intern, talk with your head doctor already and tell her that I’M NOT GOING!”

“Your lungs are back to your baseline, there is nothing else that we can do for you right now.” But she wasn’t having it.

“But I don’t have a way to get home.”

“We can give you a taxi voucher, like we usually do.”

“But the pharmacy won’t be open for 2 days, so I won’t have my meds.” She was throwing out any excuse she could find. She knew the pharmacy defense was likely to work on us.

“We can make sure that you have enough at discharge until the pharmacy opens.”

Just then, she began to pant and breathe heavy. She was complaining of chest pain and immediate severe shortness of breath. I quickly listened to her lungs and heart, but I heard nothing out of the ordinary; her three alveoli were functioning as good as possible. Whether she just spoke the magic words of “chest pain” to get our attention, confused her emphysema shortness of breath with a heart attack, had some heartburn, was having a panic attack, or was actually having a heart attack, I can’t for certain say for sure, but I have my theories. The best way to stay in the hospital is to complain of chest pain when you have legitimate risk factors, as she did. We would have to ensure that she did not have a heart attack with some tests. It looked like she and I would be spending Christmas together after all.

The morning of Christmas Eve, before my interaction with Regina, I cried as I was getting ready. I didn’t want to work on Christmas the following day. The guilt of leaving my family on the holiday briefly brought on the thought of calling in sick tomorrow, but that would be horribly cruel to my team and whoever would need to be called in among my resident colleagues to take my place on the biggest holiday of the year. I don’t know if I actually had the realization at that time or if I have since attached this to my intern-self retroactively, but this proved to be part of the erosion of the structure of my own spirit, acting as a symptom rather than an isolated occurrence of my unraveling psyche. I prayed for a miracle.

That day we ended up discharging a large percentage of our patients without admitting very many. Because of the lighter patient load for Christmas, my senior resident then acquiesced to my greatest current, but unspoken, desire—I didn’t have to work on Christmas. My fellow intern had volunteered to work the 25th if I would work on January 1st. He didn’t have kids and so didn’t feel too bad about missing any Christmas day festivities. While it was only a small step in healing my overburdened psyche, it produced immediate dividends in my well-being. I don’t think that even now he knows that he was an answer to heavenly plea.

As per Regina’s desire, she was not alone on Christmas, even though all of her tests unsurprisingly came back normal. As per my desire, I also was not alone on Christmas. I got to watch my kids open their presents, and I’m glad that I did. For at least one day, the structure of Regina and my alveoli-laden lives did not deteriorate, and in our own weird ways, we proved to ourselves that we do exist in some meaningful social level. I’m not sure that Regina and I are very different after all.

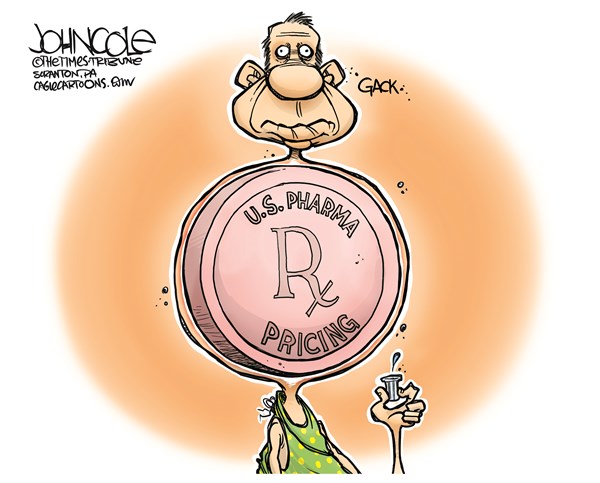

High Costs (and Profits) of Prescription Drugs Make Me Sick

This is my latest post on the AAFP’s Fresh Perspectives Blog. You can also check out my recent Scope Radio podcast on this topic with Erin Fox, PharmD.

Reggie is a spunky, 38-year-old patient of mine who makes my clinic day more enjoyable. His collection of chronic health problems — including type 2 diabetes, near-complete hearing loss, bipolar disorder, active hepatitis C from prior IV drug use with no current liver fibrosis and chronic migraines — certainly make life more difficult for him, making his buoyant personality all the more remarkable.

Reggie and I have been working on these conditions since I started practice a few years ago — well, except for the hepatitis C, even though he does have a treatable strain. Because many of his other conditions would likely be significantly worsened by the standard treatment regimen of interferon and ribavirin, he has never been a good candidate for therapy.

Likely every family physician has stories like this, whether about patients with hepatitis C or other conditions requiring expensive medications. If every person in Utah afflicted with active hepatitis C disease were to receive treatment with Sovaldi, it would consume the entire Medicaid budget for my state. The average cost of medications for complicated conditions such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis is now higher than the median household income in the United States. So it’s no surprise that rising prescription drug costs are now the biggest health care concern for the general public.

After years of ignoring the problem (and, in some cases, contributing to it), politicians and policymakers have started discussing the crisis. HHS recently hosted a summit on prescription drug prices. Presidential candidates have weighed in on the topic in their stump speeches and debates. A Senate committee recently grilled President Obama’s nominee to head the FDA on this issue. All this may or may not lead to change, but at least the issue is reaching a national level of discourse.

But what has led to exorbitant price increases in medications? Why do Americans pay so much more for the exact same medications than do patients in other countries? There are multiple likely culprits:

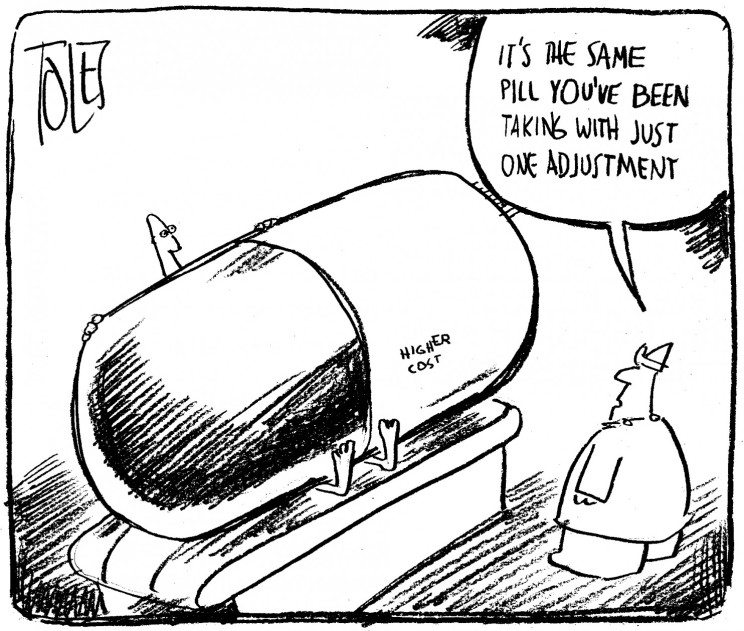

- Price of innovation — It simply costs money to come up with new, effective medications, but how much is “reasonable” for a company to spend on research and development of new drugs is a controversial question. Many think that the investment drug companies claim to make in R&D is an excuse to reap higher profits, whereas others argue it is simply the cost of doing business.You can imagine my excitement when many new treatment regimens with considerably fewer side effects began receiving FDA approval, beginning with sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) and simeprevir (Olysio) in 2013. I began coordinating with a hepatologist at that point to get Reggie the care he needed, but we quickly discovered that none of these regimens would be approved for him because of the exorbitant cost, reportedly more than $84,000 for a 12-week treatment course. Reggie is covered by both Medicaid and Medicare, but neither payer would cover the cost because, ironically, his disease had not yet progressed far enough.

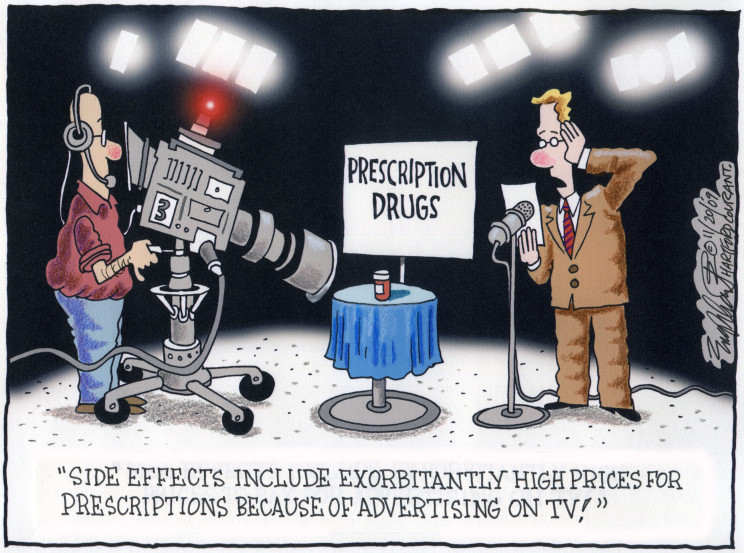

- Direct-to-consumer advertising — The FDA loosened regulations on advertising pharmaceutical products directly to patients in 1999. There has been a significant increase in drug prices since that time, but it is unknown if the agency’s action was the cause. The AMA recently came out against this practice as have many patient advocacy groups, and the AAFP says direct-to-consumer ads should not mention prescription drugs by name.

- Patent laws — Many laws passed during the past two or three decades have lengthened the life of pharmaceutical patents. This keeps generic medications from coming to market until much later, allowing the developing company a larger profit on its product. And 27 percent of generic medications increased in price in 2013, including the long-time generic medications doxycycline and pravastatin. Because of this, it is unclear if changing patent laws would significantly decrease prices. Nevertheless, the higher prices of brand name drugs remain under the purview of the pharmaceutical company for many years.

- Changing insurance market — The long-term trend in health insurance is leading to more out-of-pocket costs, including those for medications. Patients may be simply more aware now of the high costs of medication.

- Medicare restrictions on price negotiations — Medicare is prohibited from directly negotiating drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, leading to significantly higher prices compared with those of national systems in countries that do negotiate prices. Correcting this is one of the most widely discussed potential solutions, likely because it is in direct control of the federal government, and because the bulk buying power of Medicare could significantly alter drug costs in the United States. For these reasons, it is my opinion that this is the most likely first step to be taken in addressing the problem.

- Reimportation ban — It is illegal to reimport medications from other countries for cheaper sale. Many Americans do travel elsewhere, particularly to Canada, to buy prescription drugs, but opponents claim that raises potential safety issues. Whether that is a significant concern or not, the limited supply of medications in other countries makes reimportation an unrealistic solution on a broad scale.

So what about Reggie and treatment for his hepatitis C? I have tried multiple avenues, but there is likely no hope for getting any appropriate regimen covered for him at this time. There is a limit to what I can do for my patients. Many pharmaceutical companies offer rebate or discount programs for medications, and occasionally, direct appeals to insurance companies (beyond prior authorizations) can be successful, but there is no easy fix to this problem.

Considering the immense power of the pharmaceutical lobby, the solution may need to come from patients up, instead of from the government down.