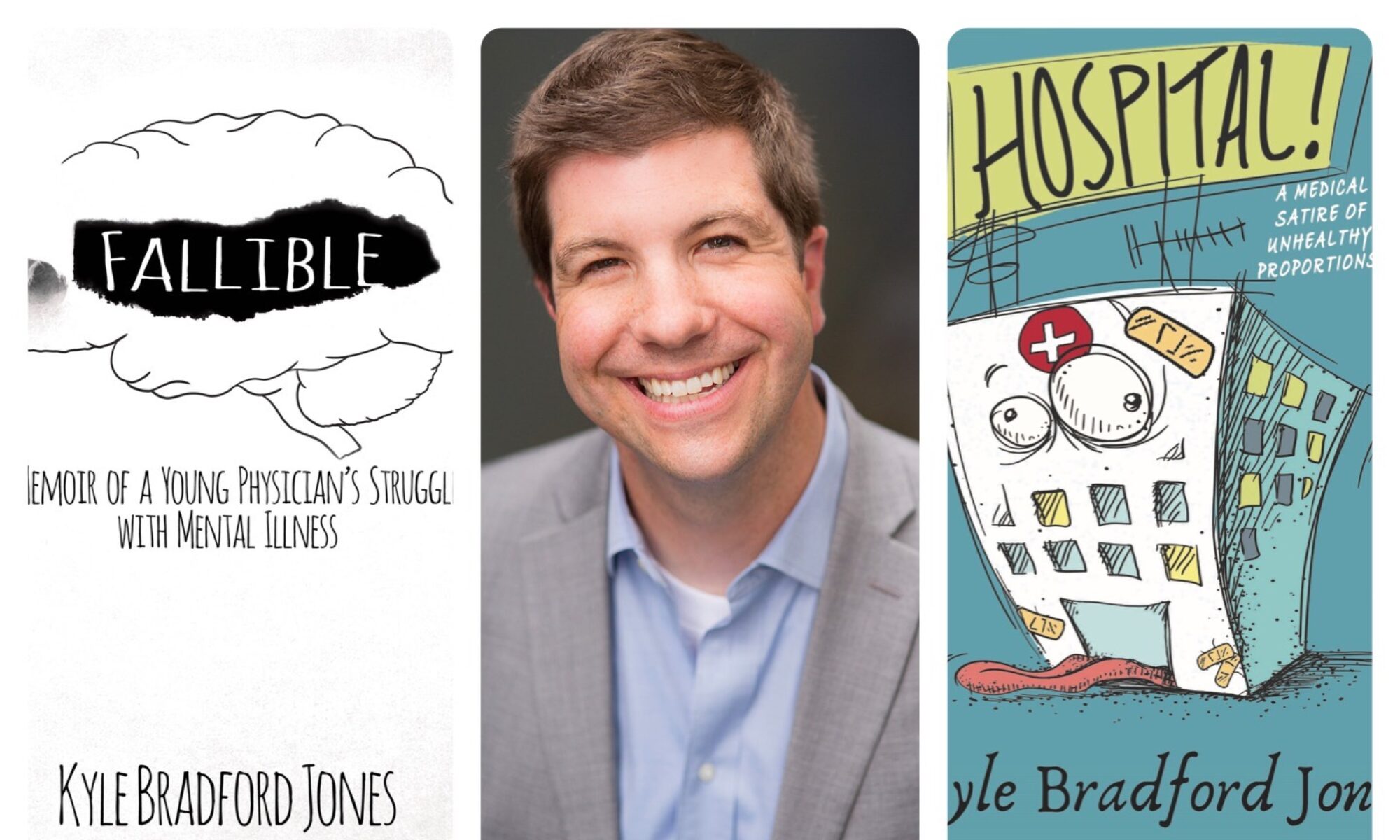

Here are the opening pages to my book Fallible: a memoir of a young physician’s struggle with mental illness. Go to the home page to find out how to get your copy of the book. Enjoy!

There are so many ways to describe hospitals that it’s hard to decide which sense I should evoke. Should I describe how cold a hospital is? I once pulled a muscle in my upper leg shivering under an ultra-thin blanket in our call room, not able to get cocooned tightly enough into the fetal position to warm myself during my short break. No, I’ll start elsewhere.

What about the sounds in a hospital? Alarms go off so constantly that they no longer mean anything. Every hall echoes with the voices of frail people yelling “Nurse!” Medication drawers click. The rubber on the sole of the various staff’s shoes squeaks against the linoleum floor. The beating of keyboards, swish of a mop, and patient’s televisions showing Wheel of Fortune turned up way too loud are unavoidable. Laced through it all are the audible grumbles of the nurses and aides and doctors and janitors and lab techs and radiology techs and ghosts of years past.

Perhaps I’ll tell you about the smell first, because it’s the most strangling of a hospital’s senses. The fragrance of a hospital is simultaneously intoxicating and revolting. There’s the aroma of cleaning products used to cover up body odor, stale air, suffering, and death. If you go farther inside, you’ll not just smell yeast—tangy, pungent yeast—growing under the fat folds of every patient in the intensive care unit (ICU), but more wade into the thick of it; it flourishes because of the near-inescapable use of antibiotics. Put it all together, and the odor sticks to the beige walls, the equipment, the lights, the charts, the computers, the curtains—the cumulative stench of years of exposure. It permeates the air; no amount of air freshener can cover the stink of health care. You can even taste the stench of failure inherent in the hospital’s very existence, leaving an imprint like a thumb pressed into a patient’s swollen leg.

The smell becomes so pervasive that you can’t wash it out of your scrubs. It’s so insidious that hospital workers rarely even notice it; in fact, it’s the absence of the aroma that creates confusion. That scent often becomes a drug. Without it, a physician no longer recognizes their surroundings.

It was in this world that my two-week stretch of night shifts had become a habitual haze. I was only a few months into my intern year, and as time marched on, it felt more like falling than making progress. I endured thirty-hour shifts, a firehose of new things to learn, the constant fear of making a mortal mistake, rarely seeing my family, and no sleep, no sleep, no sleep. My brain yawned, my eyes twitched, my thinking dulled. My concentration flitted in and out. I sometimes stared blankly, void of all thought, my body having shifted into mere survival mode. I was like Albert Camus’s Dr. Rieux tirelessly treating the plague, somewhat conscious of a “bleak indifference steadily gaining” on me in my fog, as I feared treating patients was becoming futile.

I also stank worse than the hospital did. I was running on waxing and waning adrenaline, often drenched in sweat with limited time for showers. Forget what the commercials say: no deodorant lasts for thirty hours in a hospital. Fumes emanated from my crotch, but maybe I’m the only one that noticed them. No, I doubt it. Perhaps the pungent aroma wafting out of the ICU and filling every cranny of the drab, linoleum, fluorescent-lit hospital covered up my odor. I could only hope.

I wanted to be the compassionate doctor who changed lives—a true healer, the renegade physician-cowboy who rides in on his stallion and knows just what to do to save the day. But that resolve, along with my ability, seemed to be slipping away. Was I be losing it this quickly? I still had over two-and-a-half years in my residency. In the meantime, I had to hold on to the hope that practice after residency was better than this.

It occurred to me that my angst was fueled by my continually disrupted circadian rhythm thanks to a constantly changing schedule. If that was true, it meant that I would snap out of it once my system returned to normal. I also recognized that my harsh lack of sleep had significantly affected the severe anxiety with which I had struggled for many years and had kicked off a nearly crushing depression that began when I started my residency. But I didn’t have time in my schedule to see a therapist, let alone a doctor to adjust my medication. For the time being, I had to wing it mostly on my own.

That was the reeking, anxious, sleep-deprived situation in which I found myself one night when, just ten minutes into a sound sleep, I was ripped awake by an overhead announcement of a code blue. Translation: someone’s heart had stopped, and that patient would die without our help.

Climbing out of the deep end of sleep, it took me a moment to realize what was happening. My eyes burned, melting under the strain of my sudden cognizance. Not only did someone’s life now hang on my immediate actions, but I couldn’t even focus on anything for more than a few seconds at a time. But no matter: the abrupt disturbance of my sleep combined with my sleep blindness and the quick realization of what lay before me combined to send the adrenaline coursing through my veins.

I quickly made my way to the long-term acute care (LTAC) facility located upstairs in the hospital. We rarely saw patients on this floor, it being a cross between a rehabilitation center and ICU stay for those who will be critically ill for a while. Despite not caring for patients in the LTAC, our residency team helped with emergencies there. It smelled even worse than the ICU.

My senior resident and I made it to the unit at the same time as a host of others—nurses, respiratory technicians, an X-ray tech, and a lab tech. The poor gentleman in question—Mr. K—was in his sixties. I knew nothing about him when I ran into his room, but quickly learned that he had developed severe heart failure from a massive heart attack just a few weeks earlier. He also had chronic lung disease, but they had removed his ventilator two days ago.

It wasn’t a pretty sight. Mr. K’s hair matted to his head from sweat, his obese body limp and lifeless, as he lay flat on his back. His skin blanched, appearing even paler next to the colorful cartoon designs on his nurse’s scrubs. We didn’t know what had happened in the moments before his nurse found him unresponsive, but our best guess was another heart attack. Based on his medical problems, he didn’t have much physical reserve to survive another large medical event; his odds of survival were slim.

As I pried my eyes open and started to see my surroundings, I noticed the tired painting of a flower arrangement on the wall. It had been there for decades, and the paint had faded. Under the buzzing lights, the light tan of the linoleum and walls seemed to exude a sense of defeat. This wasn’t an environment made for healing. Instead, it was purely practical, a time capsule that stood in contrast to the newer, brighter, homier, even sexier hospitals of today.

We went to work resuscitating Mr. K. My senior resident, the emergency department (ED) physician, and I led the team of secondary staff as the only physicians present. Everyone there was trained to follow the various procedures involved in bringing back the patient, each depending on different levels of heart and lung function. I gladly let one nurse do the intensive work of chest compressions while my senior resident and I worked on inserting a tube into Mr. K’s throat to assist in his breathing. The loud crack of his breaking ribs filled the room, though I was used to that sound by now. It’s a sign that compressions are being done correctly. The ribs protect the heart and lungs from outside trauma, but Mr. K’s heart needed the trauma if he was going to revive.

We repeated the procedures over and over to get his heart pumping again: evaluate heart rhythm, provide chest compressions, push air into his lungs, administer support medications (such as epinephrine), get labs to determine the root cause and thus ultimate treatment, consult the electrocardiogram, and so on. Mr. K’s heart was not beating, but despite what you see on most television medical dramas—“Live, dammit, live!”—shocking the heart is not always what’s needed in these situations.

That was the case with Mr. K. We hoped all our efforts would create a cardiac rhythm that would either start the heart pumping or would enable it to respond well by restoring normal rhythm. But this gentleman was not responding to our efforts. He was dead, and it looked like he would stay that way.

The question of how long to perform advanced cardiac life support is always a tough one, and there is no definitive answer. I’ve taken part in a code that lasted eight minutes, and I’ve participated in some that lasted for more than an hour. Ideally, the time spent reviving someone is based on a solid ethical framework and compassion; more practically speaking, it depends on the preferences, disposition, and how busy the physician in charge is. Sometimes resuscitation efforts continue until a loved one arrives at the hospital in time to see the patient “alive” and say their final goodbyes. It has even been found that loved ones have a greater sense of closure and finality when they see the resuscitative efforts, though the organized chaos can also go the other way and cause ongoing psychological trauma to those who see it. There’s just no simple solution.

After about thirty minutes of trying to revive Mr. K and having gone through the prescribed procedures multiple times, the ED physician called it—Mr. K was dead, and we finished trying to save him. I was relieved. I had had enough. My body still wasn’t even fully awake. At multiple points during the resuscitation, I had a thought I never imagined I would have—one I feared proved that I wasn’t the healer I aspired to be, and that I would never be that healer.

I just wished Mr. K would die so we could stop and get some sleep.