Note: This was first published in December 2014 at the Fresh Perspectives blog, but still holds true

Do you remember what a huge news story Ebola was one year ago? For a while, it seemed like the virus was the only story in the news.

In fact, Ebola was likely a top-three — and possibly the biggest — news story of 2014. It certainly was the biggest story in medicine.

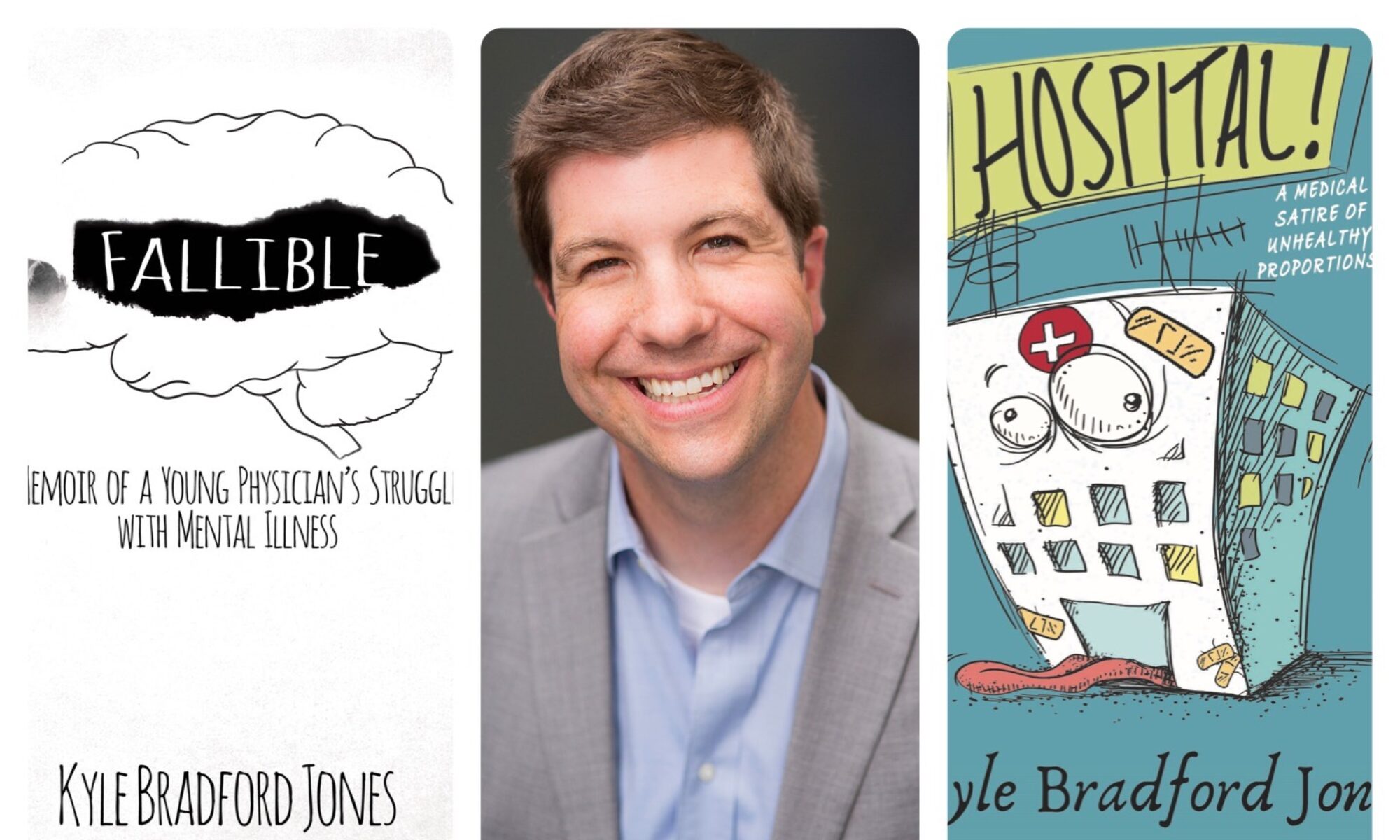

|

Image courtesy NIAID Produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), this digitally-colorized scanning electron micrograph depicts numerous filamentous Ebola virus particles (blue) budding from a chronically-infected VERO E6 cell (yellow-green). |

The coverage in cable news, print, talk radio and online media illustrated how our health care utilization is influenced by the news. Some hospitals experienced an increase in emergency department visits due to patient concerns about potential Ebola symptoms. At one point, in fact, the CDC was logging 800 calls a day about potential cases of Ebola infection.

None of those calls panned out.

The irony was not lost on physicians who tried to educate concerned patients about Ebola and the need for a vaccine to combat the virus when the same patients then refused a flu shot. For the record, there have been 10 cases of Ebola treated in the United States and two of these patients died last year. By comparison, the CDC reported that as of December 2014, more than 1,000 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations and seven influenza-associated deaths among children had occurred, despite it still being early in the flu season. During the week ending Dec. 6 alone, the CDC said there were more than 3,400 influenza-positive tests reported to the agency.

So how can physicians — and as educators of future physicians — deal with demand for health care that is influenced by the media?

Well, we shouldn’t trust the “facts” provided in news reports as completely accurate. We’ve all seen stories about new medical studies or other health-related topics presented in the media in an inaccurate way. Oftentimes, the details are misunderstood, or worse, the entire point of the study is misrepresented.

Remember in December 2013, when Katie Couric used a rare side effect of the HPV vaccine to imply that the vaccine was too dangerous and shouldn’t be given? Stories like this are too common. As physicians, it is our responsibility to know the facts so we can properly educate our patients and the public, which means going to appropriate, evidence-based sources for information.

We should be able to put health care concerns into perspective for our patients. As mentioned above, some Americans were mistakenly more worried about Ebola than influenza. We know that even though Ebola is scary and yes, dangerous, we all have a much greater likelihood of facing significant morbidity — and even mortality — from influenza.

It’s critical that we be able to explain these facts to the patients we care for so they can make informed, proper decisions about their health. We can provide information on these topics not only during office visits, but through our local traditional and social media outlets.

If we can work with the media to inform people about real health care concerns and then use that leverage to improve health, we can squelch mass hysteria. For example, we recently learned from the CDC that 2014‘s influenza vaccine was not as effective as we would have liked. Even though the vaccine will still provide some protection, the news reports likely have turned many people off from getting the vaccine.

Before the CDC shared information about the vaccine’s shortcomings, there had been — by comparison — little coverage in the news about why we should be vaccinated against not only the flu but other diseases, as well. Physicians have the expertise and the clout to be able to drive these discussions instead of merely reacting to them. We should all be more involved in steering the conversation toward true health needs that will impact our patients and our communities.

Inaccurate medical information in the mass media can be difficult for patients and physicians to deal with and often causes frustration. Still, as physicians, it is our responsibility to educate and inform people about the realities of media-driven health care utilization.