This is the fourth installment discussing my experiences working with Ukrainian refugees in Poland. Go here to see the other entries. More pictures of my particular group can be found here, here, here, here, and here.

Not only have Ukrainians shown a remarkable resilience in the face of such terrible atrocities, but they also continue to have a great sense of gratitude during these times. Every single Ukrainian that I spoke with in Poland (dozens, if not hundreds) all expressed sincere thanks for any help they were receiving. Tears of joy and relief came amidst tears of fear, sadness, and anger.

Many of the people I met had a sense of wonder that anyone would care enough to help. They figured that no one in Western Europe or America would know where Ukraine was, or that it even existed. “We’re here with you,” was all I could muster in such moments.

One woman told me of leaving Mariupol the day before with her daughter and grandson. The battle was still intensely raging at that time. She cried as she related the death of her husband, who happened to be the only one home when their apartment building was bombed just a week before. Her son-in-law was fighting, and she hadn’t received any word about him for weeks. She motioned to her sleeping grandson, all of nine-years-old, as she expressed horror of what was to come of his life. There was no plan yet as to where they would go, for how long, and if they could ever return to their homeland. And yet, in the same breath, she spoke of how grateful she was that they had a place to stay, someplace warm, with beds and blankets, and food. She marveled at it. She was so thankful, even just to have someone to listen to her.

Merely minutes after talking with her, I met another woman with a similar story. Her husband had died well before the war. She was in her seventies and confined to a wheelchair. She had arrived a few weeks previously with some family. Given her poor health, she was unable to move on to another place, but was worried about holding her family back. They were working on visas to another country, with the plan that she would likely stay put in the shelter in Warsaw. She was so scared, and had to completely depend on others for everything. And yet, instead of expressing dismay or anger or cursing God or anyone else, she told me how glad she was that she was in the center, that she had a place to get the support she needed.

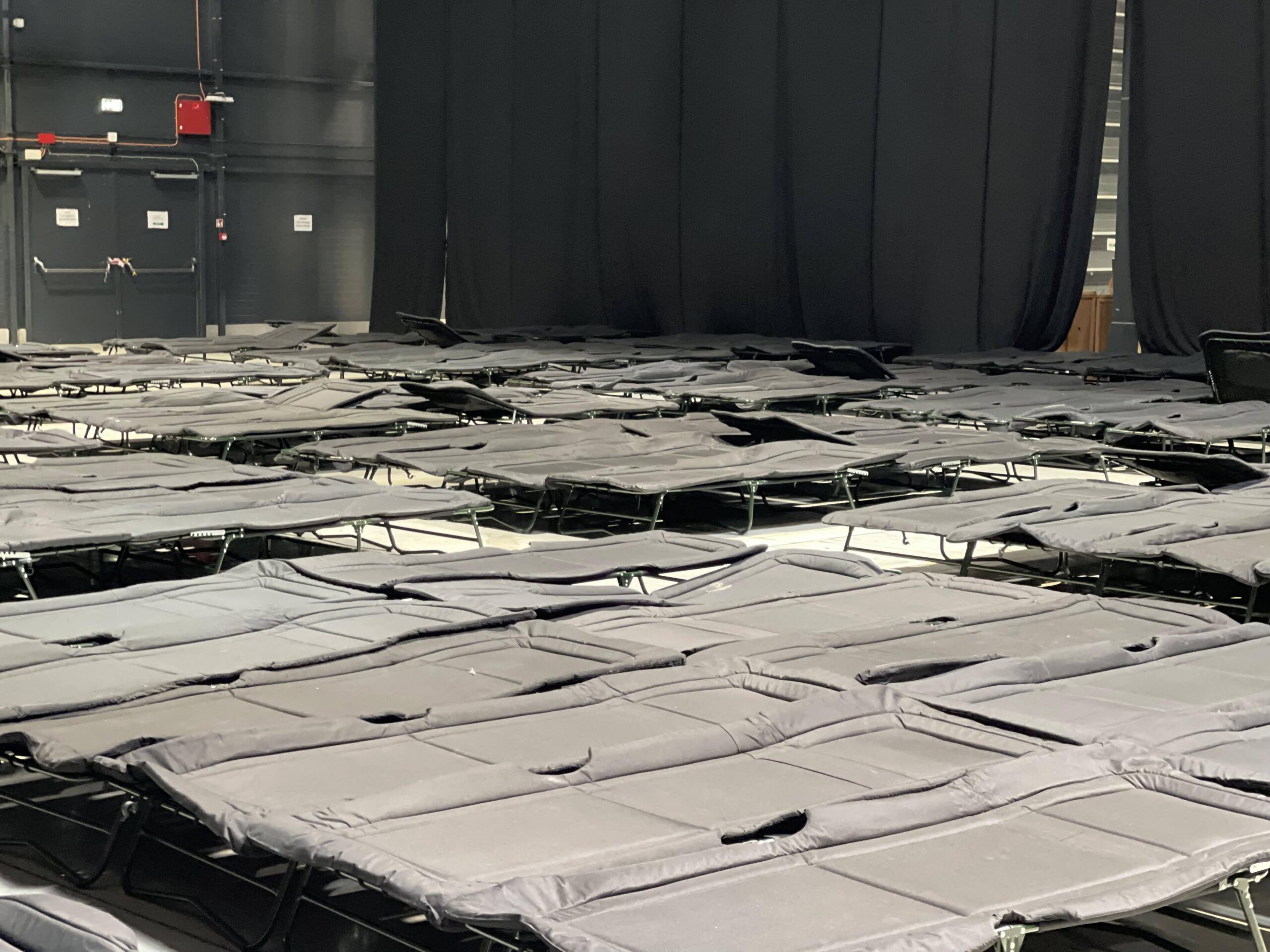

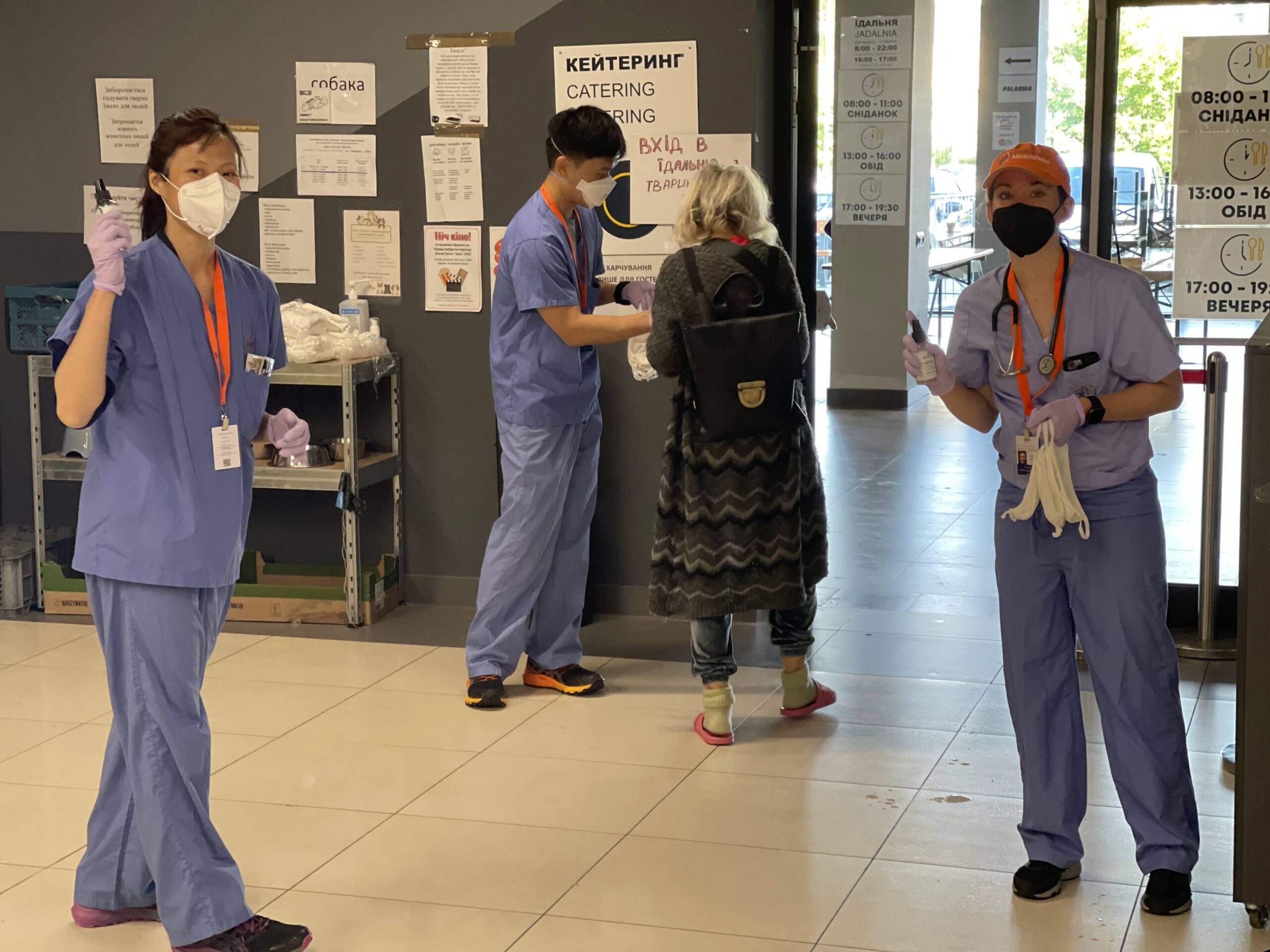

The center where we were included cots to sleep on (see below), three meals a day, our medical and dental clinics (which included many medications available for free), free glasses, visa applications and help for multiple different countries, laundry, clothing, and play areas with toys, among other things. It certainly wasn’t an ideal location for people to stay, but they all seemed grateful to be there.

I dare say most people wouldn’t react this way in such circumstances.

Just some of the many things offered to refugees at the center: